In Discussion with:

Jessie French

Building a Radically Sustainable Seaweed Future

Jessie French interview with Anaïs Lellouche.

Special thanks to Katya Conrad

Jessie French.

Amelia Stanwix for the Design Files.

Courtesy of the Artist and Design Files.

“There’s lots to gain from being curious about the world.”

Anaïs Lellouche

How did you come to the idea of seaweed/algae-based plastics as a material for your works?

Jessie French

Between climate science literature, post-denialism and a healthy dose of speculative and science fiction, I’m interested in new ways of living on this damaged planet—damage which we humans are largely responsible for—among other living things. In 2015, I began beekeeping and gradually became part of the natural beekeeping group Honey Fingers Collective. We explore the intersections between farming, food, art, history, design and education, and I learned the honeybees that humans rely on to pollinate up to 80% of our staple food crops are facing population collapse. If bee populations continue to decline, we will have big problems in sourcing enough nutrients to keep humanity healthy; for example, most human sources of vitamin C are currently pollinated by these bees.

This is where seaweed comes in: Below the water, there is a plethora of other sources of nutrition. However, many of these sources face similar issues to the bees with threats due to warming, acidifying oceans, proliferation of other species of ocean flora, pollution and some human fishing practices. So, my interest in seaweed grew from the similarities and links between the threats that many species of plants and animals face now, as well as the opportunities for change.

In 2018 I’d begun looking into bioplastic recipes and in 2019,

I began experimenting with some. By far the most success I had was with algae-based recipes. Towards the end of that year, curator Anaïs Lellouche sent me details of an arts residency in Morocco, La Pause. I applied with an initial idea of thinking about desert bioreactors as a potential nutrient-dense food source that could be grown relatively easily no matter the soil beneath it. Months later, when I was accepted into the residency and by then, had been delving much deeper into algae-based bioplastic recipes and material tests, as well as researching the ingredients I was using.

By extremely lucky coincidence, I had discovered that most of the world’s supply of the algal polymer I was using comes from Morocco.

The work I planned to do on the residency shifted focus researching these supply chains, particularly the sustainability of them, as well as continuing to experiment with materiality and creating larger-scale hanging artworks and objects with organic substrates in them such as soil, olive pits or macroalgae.

AL

Do you think art has often been kept separate from sustainability practices as well as science?

What do you think is the importance of promoting interdisciplinary art practice?

JF

Certainly within art, my work is often categorised as sustainable, but in reality, I believe this should be the norm rather than the exception. As artists, we make choices about the materials we use and with this opportunity to make choices about our work and studio production, it is also our responsibility to consider the impacts these have on the world around us.

As for art and science, this is a relatively recent distinction. This kind of slicing up of disciplines is a historically new practice. I think there’s lots to gain from being curious about the world and how it works in general, and not bring restricted to one distinct path of knowledge. Retrospectively, artists have been responsible for a number of scientific breakthroughs and discoveries.

In the Renaissance, for example, artists were far more readily able to study on human bodies than anatomists were, as the latter were expected to follow and teach the cannon of Galen. There are records with evidence that some artists, like Leonardo di Vinci of this time received payment for work in access to human bodies they were able to dissect in order to study the human form for artistic purposes. Coming at anatomical knowledge without the ingrained training of the time meant that they approached it without conceptions of received and accepted views of what they were looking at.

A vast amount of new knowledge was discovered in this way.

More recently, there is a broad body of work in the philosophy of science dissecting how interdisciplinarity – both conscious and unconscious – can tangibly aid in scientific practice. Ethnographer and former dancer Natasha Myers describes how protein modellers use their bodies to contort into molecular positions to help them decipher x-ray crystallography of proteins.

These same overlaps work in a multitude of ways. The merits of knowledge about a range of practices, bodies of knowledge and experiences all builds into how we approach things. More interdisciplinarity leads to greater diversity, innovation and generative critical views of how things are done.

“As artists, we make choices about the materials we use and with this opportunity to make choices about our work and studio production, it is also our responsibility to consider the impacts these have on the world around us.”

Jessie French - Other Matter, Process.

Photographer: Pier Carthew.

Courtesy of the Artist.

AL

What is the biggest obstacle in working with this material?

JF

There aren’t many guides for working with this material, and those that do exist are largely experimental and not focussed on producing specific refined aesthetics outcomes.

The recipe I devised for the purpose of creating the algae-based bioplastic material I use, as well as the techniques I employ for moulding and making very large-scale sheets, have been equally challenging parts of this project. There were no resources or mentors to learn from, I had to build this knowledge through experimentation.

Technically intricate, the processes required for moulding a workable, functional utilitarian object of high strength out of this kind of material were developed through a laborious, iterative process of exploratory experimentation. I spent over six months in the studio, trialling and toying with different variants in order to achieve a successful outcome.

At the end of this process, I now have a process and knowledge of a range of recipes and techniques I can use to achieve a range of outcomes that can be adapted to a variety of material substrates that can include by-products of food production or craft practices such as coffee grounds, sawdust or metal shavings.

“More interdisciplinarity leads to greater diversity, innovation and generative critical views of how things are done.”

AL

What role do you think aesthetic plays in creating sustainable materials?

JF

Aesthetics are hugely important to adoption for new materials. Materials firstly must be functional, but the look and feel are often what gets them across the line in decision making – both in the first instance as well as the final deliberation.

The techniques I employ to make my work set them apart. The pieces I make are visually distinctive, refined, minimalistic objects, accentuated by unusual patterns and shapes, delicate detailing and light refracting transparency. The organic patterns that detail these vessels are coloured by 100% organic, completely biodegradable ingredients.

The interest and success of my tableware series highlights that the interest in sustainable and innovative materials is a shared one, but also that the look and function of these are equally important.

AL

OTHER MATTER is unique in so many ways including being able to address the distinctive specificities requested by customers. How are you able to meet these specific needs?

JF

It’s incredible to be able to put the skills and knowledge I have developed for my own work into use to contribute to other projects. Often working like this pushes me into developing new applications with what I already know, extending what is possible.

Being able to work on projects in a way that I can support organisations or projects to prototype replacing petrochemical plastics with sustainable, recyclable materials is phenomenal. A large part of my artistic practice dwells on a speculative future, however ironically, the work done towards this has reached into the present with immediate applications. Having an artistic practice, and all the research, thinking and imagining which goes into it, feeding into other projects give the whole work greater meaning.

My modes of practicing for myself as well as lending this expertise to other projects exist symbiotically, each building on the other.

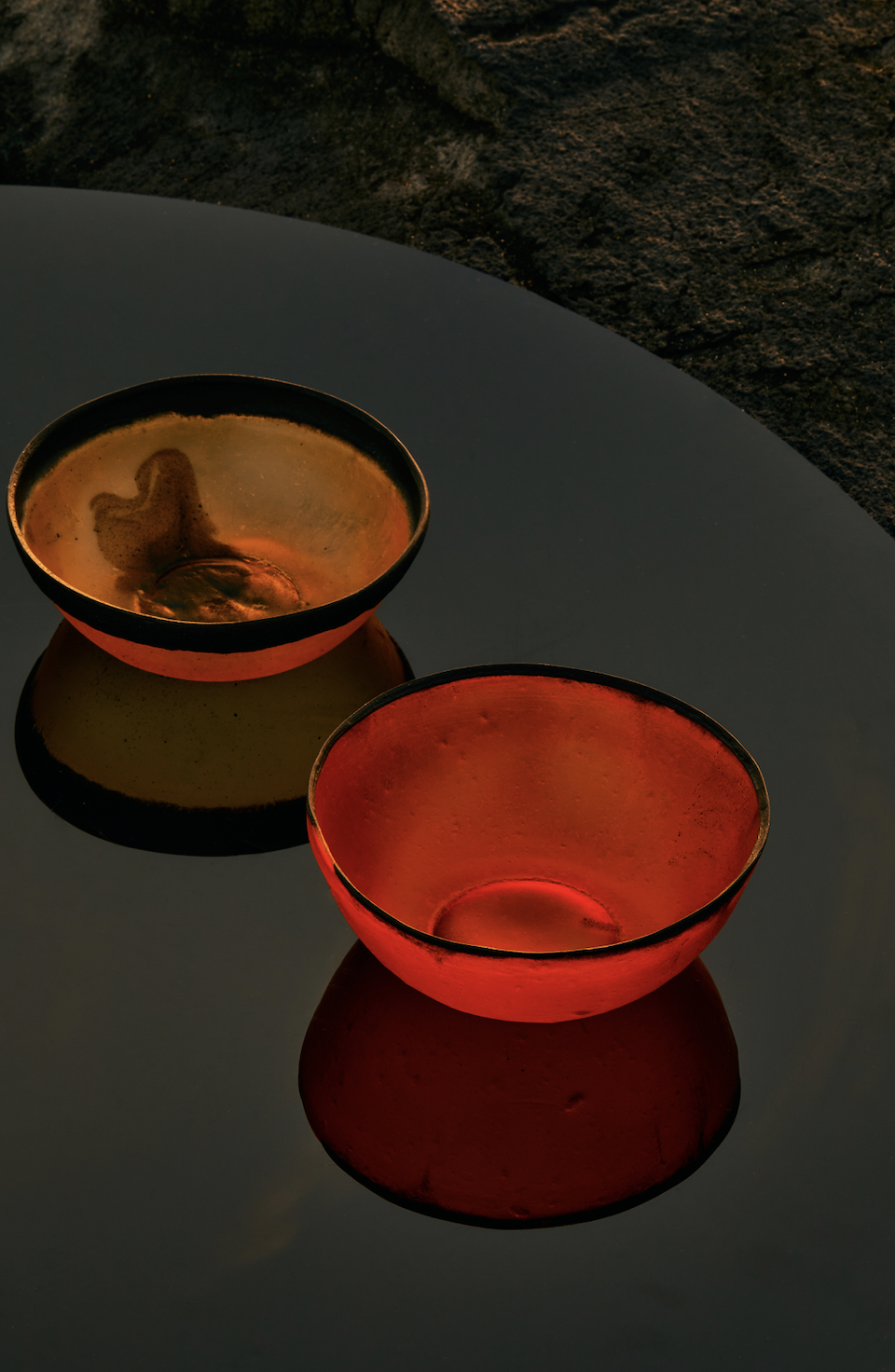

Jessie French - Other Matter, Algae bioplastic vessels, 2021.

Coloured with athrospira planentis and dunaliela salina microalgae.

Photographer: Pier Carthew. Art Director: Thalia Economo.

Courtesy of the Artist.

Jessie French - Other Matter, Algae bioplastic bowls, 2021.

Coloured with athrospira planentis and dunaliela salina microalgae.

Photographer: Pier Carthew. Art Director: Thalia Economo.

Courtesy of the Artist.